Lawyers Guns and Gruel by C.M. Kushins

George Gruel: Standing in the Fire

Warren Zevon’s famed aide-de-camp discusses his new book, rock and roll photography, and life on the road with music’s original Excitable Boy

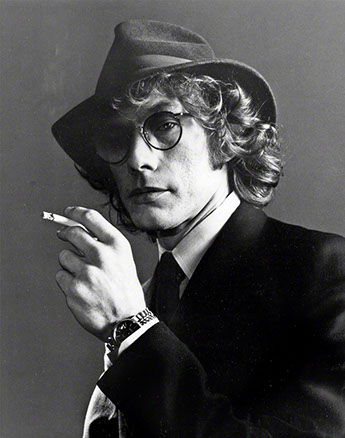

August, 1980.

Warren Zevon is smoking a cigarette outside the Roxy Theatre in LA. He’s in the middle of playing a seven-night stint, the tail-end of a massive tour to promote his latest release, Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School. The shows are a sell-out, with countless celebrity admirers added into the mix. Last night, Tom Waits wrestled John Belushi to the floor of the men’s room during Warren’s set. No one bothered to ask his motive.

At thirty-three years old, this is Warren in his prime: the excitable boy, the offender – the electric werewolf. At this moment, however, that notorious outlaw lycanthrope is nowhere in sight. Maybe he’s at Trader Vic’s. Instead, a baleful twilight hangs over the Sunset Strip, strangely quiet as a Sabbath lull as Warren, in his “off-stage” incarnation of sweatshirt and bandana, is getting his bearings for tonight’s rock n’ roll spectacle. And this limited engagement is being recorded for a live album release no less.

Looking across the street, eyeing The Rainbow Bar, tonight’s set-list rolls across Warren’s mind and he takes another drag off his cigarette. He looks up, slightly startled, to see George Gruel – best friend, tour manager, “aid-de-camp” – with camera in-hand, stealing a quick candid shot of this calm before the storm. The final image – high contrast black and white, with the swirl of cigarette and sewer grate smoke ghostly dancing in the light of the Roxy’s neon – is sure to please a film noir buff like Warren.

Gruel almost always had his camera on him in those days. We’re lucky he did. Today, Gruel – now a renowned professional photographer and graphic designer – admits that there was always a fine line between exploiting the rock star who called him “friend” and capturing the truly guarded, human moments that Warren allowed during their many years on the road together. It was a matter of trust, says Gruel, real trust. And it’s easy to see just how deep that friendship and intimacy ran: when the record of the Roxy performances was released the following year as the critically-acclaimed Stand in the Fire, everyone could hear Gruel’s status shouted for the ages during one of Warren’s best-loved signature songs, “Poor, Poor Pitiful Me” –

“Where’s George Gruel – my road manager, my best friend? Come on out here, George"! "Get up here and dance – get up and dance or I’ll kill ya!” I said the last part

The praise may have been great, but Gruel had already made his bones in the world of rock and roll in spades. He’d studied photography and art in Michigan and, after only a single visit that left an indelible mark in his mind, returned to San Francisco in 1971 to soak up the local culture and make connections within the city’s thriving art world. Those connections were of the highest order from the very beginning, from living with Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead in Marin County to contributing concert photos of Bob Dylan’s 1974 tour to the published anthology, Bob Dylan Approximately. Later, working at Fred Walecki’s legendary guitar shop, Westwood Music, Gruel was constantly surrounded by crucial members of rock and roll royalty. In 1978, Warren Zevon, hot on the heels of his smash hit single, “Werewolves of London”, wandered into the shop and he and Gruel hit it off immediately. It wasn’t long before the two – both passionate artists with mutual affections for music, hard living, and the intense trappings of the rock and roll lifestyle – were fast friends, with Warren formally asking Gruel to join his traveling tour crew as manager. I was on the road for the last part of the 1978 tour. It ended and I was working at Westwood Music and Warren walked in

Gruel would hold that post until 1983, through some of Warren’s most notorious and difficult years – days and nights of fast fame, followed by an even faster downward spiral of disappointing record sales, booze, women, a divorce, and a highly-publicized intervention which would save Zevon’s life. As both road manager and confidant, Gruel was uniquely privy to it all.

Now living in Upstate New York with his wife, Jan, Gruel recently took a long, hard look at his years with Zevon and composed his memories, anecdotes, and copious unpublished photos of that time into his first solo book, Lawyers, Guns, and Photos, newly published by Big Gorilla Press. For Zevon fans and all lovers of solid rock and roll photography, the book is a revelation, with enough trivia, imagery, and fly-on-the-wall intimacy to bring the excitable boy himself back to life for anyone who opens its pages.

When I send an email to Gruel for an interview, he not only responds with his famed courteousness and humor, but tacks a philosophy to the bottom of his letter:

“Images have always been the fabric of my life. I see photos everywhere I look, all day and all night. I frame the visual without even trying, it just makes seeing more enjoyable. I have frames around almost everything I see. I don't ponder the framing, it just happens. Life is one large rich gallery to me.”

Taking time away from his busy schedule – which currently includes a major book tour to promote Lawyers, Guns, and Photos – Gruel calls me the following week and invites me into that personal gallery of rock and roll memories…

When you were still a study of art and photography, was it ever a goal to get into the world of photojournalism, especially with an emphasis on the world of rock and roll?

No, not at all, actually. I was more into advertising photography at that time. I was originally in Detroit and we were taught by working professionals who were all in the car business, which I still find very interesting. Once I got to school, I got really into straightforward photography, and I really liked that – you know, showing “life’s rich pageant” [laughs]. But I just kind of got into it. I discovered that, even though I’m a pretty large man, I could become invisible in a room with a camera.

That’s pretty much the best quality that a photographer or a journalist can have, isn’t it?

Yeah, definitely. I’m not sure how I pulled it off, but I generally like people and talking with people and figuring out people – so that was the appeal. I should really be wearing a shirt that says, “I’m a fun guy.”

So after school, how did you eventually find your way to Los Angeles and the world of rock and roll photography?

Well, I had been living with Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead. While living there I met Stephen Barncard, who was a producer and engineer who did Crosby and Nash and [Grateful Dead] albums and stuff, and he had a friend – a woman he was recording – named Valerie Carter. She did a couple of solo albums and was good friends with Jackson Browne and Lowell George and she moved to Southern California. A bunch of friends were going, too, to go out on tour, and said, “Do you want to go with us?” I went, I was the only crew person on the trip, and I was still taking pictures the entire time. So, I made contacts through all of this – it was maybe 1977 – and I eventually met Jackson’s road manager at the time, and some other people. I was working at [Westwood Music] when I started by stint with Zevon. He came in one day, we started talking, and he finally said, “Would you like a full-time job on my tour?” I said, “Doing what?” and he goes, “Taking care of me, basically.” I went and I’ll never forget my first job on the road with him. I remember Warren’s wife, Crystal, going down the hallway to get vodka for him out of the bar … He was in the middle of a very serious alcohol problem. But, he still had this wonderful wit and humor about him that really was just wonderful.

Had you worked as road crew before?

I initially went to school for design in Michigan and, basically, I went on a sabbatical to San Francisco. It was supposed to be a month, but I went to my parents and said, “I don’t want your money, just your blessing,” and made the move. I showed up in a Chevrolet Vega – a ’71 or something – and I traded that for a gram of LCD [laughs]. That turned into a lot of hits and a bunch of money; went to Missoula, Montana and bought a panel van; then, was shooting pool with Bob Weir’s wife, Frankie (Sugar Magnolia) who was starting her own little country band, and got a job hauling equipment.

That’s how I got into that.

Was Warren aware that you had been a photographer first and that you were still carrying your camera, looking to snap photos on the road?

Not at all, which was interesting. It was after he realized that I was doing it and saw some of the photos that I had that he said, “Keep shooting – these are really good.” And he loved having his photo taken [laughs]. He was a rock and roller and was used to having his photo taken and he also trusted me. Warren also knew that if there was something weird going on, I wouldn’t be shooting that, you know, like paparazzi or something.

Looking through the photos in your book, I could see that they were candid shots, but also that there was a very real form of trust and intimacy in the photos themselves. That’s something that most photographers don’t get to achieve.

I had friends who were rock photographers who would come over and see my work and I’d see theirs, and their stuff really wouldn’t have that same intimacy. Warren and I were basically best friends who lived together, so that really worked nicely.

© George Gruel 2020

You lived with Warren for a good amount of time while working as his road manager. Most people know about his addiction problems at that time, too. Did that situation ever create scenarios where you made a conscious decision to leave the camera alone and not shoot everything that was going on?

That’s exactly what I mean about trust, that “trust factor.” I got him through a detox right there at home, and that was hell, since he didn’t want to go into rehab again. So, I had to keep living with him so he wouldn’t die … A lot of photographers may have gotten into a comfort zone about things like that, like war photographers being objective and slipping away into their photography. But I could never do that with Warren.

You talk about that type of objectivity, which is funny since there are photos in your book with Warren posed alongside Rolling Stone writer Paul Nelson. Nelson was a great writer, but even admitted having a similar problem after becoming friends with his own subject – even helping organize Warren’s intervention, which is a humane line that a lot of writers would be afraid to cross.

It’s interesting that you bring that up. There’s a full contact sheet in my book of those photos of Paul with Warren, posing with their guns and stuff. For the longest time, I couldn’t find that sheet. Then, there was a recent biography on Paul and I got a call from the author [Kevin Avery] asking if I have any rare photos of them together. I didn’t have those photos, but I found out that Paul’s son actually had them! I let them use a few in the book, but I finally got that contact sheet back recently.

It must have been some major process going through all of your old photos and memorabilia for the book. What was it like putting it together and seeing all the old work?

I’m not really a pack-rat, but I saved tons of stuff, tons of photos over the years. I didn’t keep anything stored properly, like sealed or anything, but luckily almost everything was in good condition. Fortunately, I’ve gotten very good at scanning and cleaning things up, so I was able to re-touch and preserve many of the photos myself. Even the old Polaroids came out well in the publishing process. I was very pleased with how they held up. But we’re just talking boxes and boxes of things – many of which have lasted through various moves across the country.

As a photographer, did you have any particular influences or other artists who, early on, you may have admired the most? I can’t help but make a certain comparison, when I see your work, to someone like William Claxton, who did all the early shots of Chet Baker.

Well Claxton was one, but my earliest influence was probably a photographer named Irving Penn. And also Duane Michaels and Robert Frank. I mean, there’s really a group that I liked. But I’ve also always been very influenced by Caravaggio’s paintings, his work with light. I never use artificial light in my photography, ever, so I’ve always admired how his paintings captured natural light especially. I’ve never owned a flash and I’ll never use a flash. If you look at Penn’s photography, I think you’ll see that same type of influence. I love dramatic lighting. Graham Nash has also become a very close friend and he helped me years ago when I started working with digital printers. He is the foremost digital printer in the world.

Graham Nash from Crosby, Stills, and Nash?

Yep. He’s actually huge into photography. His first digital printer is now in the Smithsonian. Most people don’t know that, but it’s a huge interest of his. Another very talented lad.

It’s amazing how artists have interest in other mediums, and how they can become so related to each other. I think that’s also reflected in how Caravaggio is an influence on your photography. Do you think you’re influence by other mediums aside from painting? Maybe music itself?

Oh, I have music going as much as I can [laughs]. It’s sometimes classical, but it’s usually loud rock and roll.

It’s a pretty big revelation that you don’t use artificial lighting. Do you ever work in digital photography, or are you a purist with film?

Both. No, I’m a fan of digital, by far. If Ansel Adams was alive today, he’d be using it. There’s freedom and the quality is there, plus the options. And one thing that I love about working on digital photography, I can give you example, is how well color can sometimes work once you’ve desaturated the photos and seen the black and white of it. I do high-end printing for people now, and I’m amazed with the detail that you can bring out in the shadow work.

Many photographers that I’ve spoken to seem to have a love-hate relationship with digital, and some swear they’ll never use it. But it sounds like you take digital photos but use the careful nuances of capturing for film. Is it that you’ve adapted the basic fundamentals of film to the newer medium?

A friend of mine is a teacher, a professor of photography and he’s been doing it for 20 years. Now he has students coming in having done some stuff on Photoshop, but not really understanding what they are doing. So, I think that it is really the same. If you want to learn the piano, you still have to know your scales. You know? Know your fundamentals, then go off and play jazz. You can’t just bang on the piano and say it’s jazz [laughs].

I think that applies to every art form. In the last issue of the magazine, I did a sit down with artists of different ages and their own mediums and we kind of agreed on that whole philosophy of knowing your medium inside and out before getting abstract.

Where you spoke with like three or four people?

That’s the one. I like hearing what different artists have to say and, usually, their strongest philosophies turn out to be the most universal ones.

Well, I had also studied illustration and painting, and I still work within that occasionally. I just recently did a really nice pencil sketch for my wife of her favorite flower. See, it’s all just images, really. Images and light and dark.

When you finished your stint as Warren’s road manager and, what called you, his “aide-de-camp”, did you immediately get back into photography full-force?

A friend of mine was one of the road managers for Crosby, Stills, and Nash and he and I both decided that we’d better get out of this business or we’ll die or overdose or something. His brother was working for ABC Films out in LA and music videos were just starting. So we both thought, let’s do this – we both know people in the business. The last video that we did was Lionel Richie’s “Dancing on the Ceiling”, which we produced, and which had a half-million dollar budget. Later, we said, let’s produce commercials, since these projects were all kind of related, and the company we worked with brought us to Albany – and that’s how I made it to New York, and I love it here.

When you were going through all the old photos and materials for the book, how did it feel to see all of it at once? All the memories come back to you while picking what would make the final cut? Was it a long process putting the book together?

In the back of the published book, you’ll see that there is a recent photo of me and Jackson [Browne] as he looks over some of the pages still in progress. That picture is from 2010, so I’ve been working on it at least that long but even before that shot. I had a lot of other work going on, but I decided at one point to just buckle down and do the work that really needed to be done – the photos themselves, making the selections, and writing the anecdote stuff. So I’d just sit in my studio going through all these old photos every night, smoke pot, and write down stuff as I remembered it. But I tried to write it in a conversational style to match the photos.

What’s the feedback been on the book and the promotional touring?

Amazing. Also having so many people in the book see the work-in-progress was an experience. One of my favorite quotes and I'm honored that he wrote, is from iconic rock photographer, Baron Wolman; “A remarkable collection of photos, of the remarkable life, of a remarkable man. And, as a bonus, George’s spot-on picture memoir is occasionally, as creatively eccentric, as Mr. Z, himself. Love it...!!! Man, you guys has some serious fun back in the day... Now, between your book and Crystal's book, I feel as if I have a very intimate picture of WZ, the man. 'Wish I had known him. 'Wish I had photographed him, but YOU did and that's the good news. The book deserves a wide read".

Do you have any advice for aspiring photographers, especially those who are looking to get into the world of rock photography?

Follow your bliss and always stay in the shadows.